The Piercing Gaze of Greek Sculptures

These millennia-old eyes were carved to see forever...

We are so used to statues being inert that we have forgotten what it means to be looked at by one.

The popular image of ancient Greek sculpture — white, pale, polished — is not just inaccurate. It is anaesthetized. It reflects the tastes of neoclassical Europe more than those of Periclean Athens. As Sarah E. Bond points out, the statues of antiquity were meant to dazzle with color:

Modern technology has revealed an irrefutable truth: many of the statues, reliefs, and sarcophagi created in the ancient Western world were in fact painted. Marble was a precious material for Greco-Roman artisans, but it was considered a canvas, not the finished product for sculpture. It was carefully selected and then often painted in gold, red, green, black, white, and brown, among other colors.

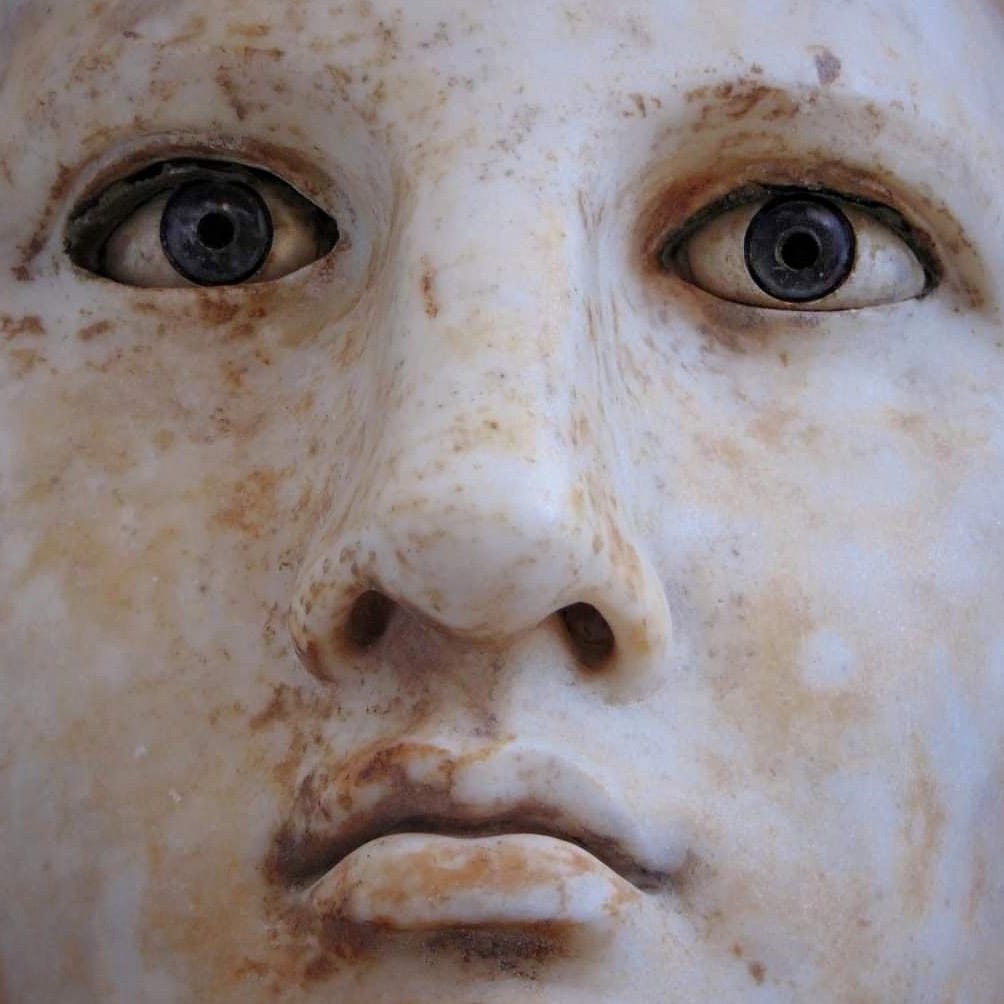

Whether we’re talking about marble or bronze, these statues were never blank. They were painted, inlaid with copper, ivory, glass, and stone. Their lips were the color of blood, and their eyes reflected light — not metaphorically, but literally. They truly “looked.”

And that matters more than we think…

Reminder: This is a reader-supported publication dedicated to spreading beauty, and it depends on your support to keep going.

Upgrade your subscription for just a few dollars a month to help our mission and access members-only articles 👇🏻

The Universal Language of the Eye

Across cultures, the eye carries profound meaning. We read focus and emotion from it — whether someone is listening or distracted, telling the truth or holding something back. The entire social grammar of human interaction flows through the eyes. As the English poet George Herbert once summarized:

The eyes have one language everywhere.

The phrase “shifty-eyed” did not emerge by accident. Nor did the idea, present in various Indigenous traditions, that the eye has the power to reveal or even steal the soul…

We gather light with our eyes — literally. And perhaps that’s why the Greeks treated them with such obsessive care. They knew, long before anyone spoke of psychology or body language, that eyes confer life. A statue with no gaze is an empty shell. A statue that looks back is something else entirely…

The modern viewer, raised on the museum-white sterility of neoclassical taste, often misses this. But those rare sculptures whose inlays survive feel very different. Uncomfortably so.

You don’t simply view them. You meet them.

The Greeks knew exactly what they were doing. To see such a statue today is to understand, perhaps briefly, what we have lost: not only the color, the lashes, the gleam — but the sense of encounter.

What follows are some of those rare survivors. Not because they are more beautiful than the rest (though they often are), but because they remind us what Greek sculpture truly was: powerful, visceral, and alive…

1. The Philosopher, 250- 200 BC

Nicknamed the "Antikythera Philosopher," this bronze statue fragment is believed to depict the Greek scholar Philitas of Cos. It was recovered from the Antikythera shipwreck, a treasure trove of ancient artifacts discovered by sponge divers in 1900.

2. Charioteer of Delphi, 478 or 474 BC

This bronze statue of a chariot driver, discovered in 1896 at Delphi’s Sanctuary of Apollo, honors Polyzalus’s victory at the Pythian Games.

It is one of the few Greek bronze statues to be preserved with inlaid glass eyes.

3. Antikythera Ephebe, 340–330 BC

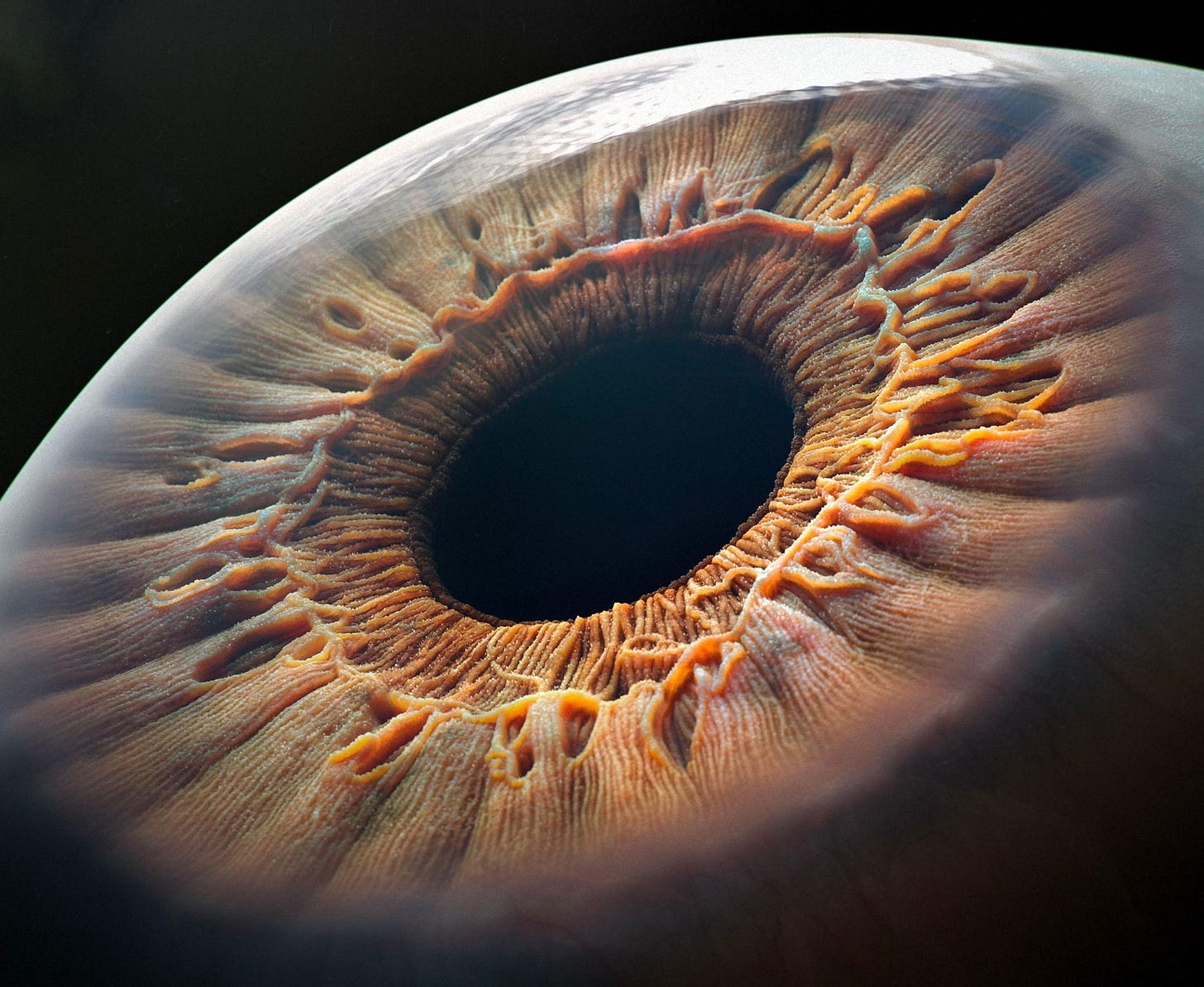

Greek sculptors often crafted eyes from alabaster and glass paste, framing them with copper strips to shape the lashes and brows.

The result is astonishing. I mean, look at this masterpiece… It feels as though those ancient eyes are still watching us, even after more than two thousand years.

4. Head of the Goddess Hygeia, 2nd century BC

Crafted by the Athenian sculptor Attalos, this marble sculpture features eerily lifelike eyes made of glass and agate, with delicate bronze eyelashes.

5. Portrait of a man from Delos, 1st century BC

This mesmerizing sculpture was discovered in Lake Palestra, an archaeological site of Delos, Greece. It’s a bronze portrait of an unknown man, featuring inlaid eyes, dating to the Hellenistic period.

6. Head of a goddess, 2nd century AD

Discovered in 1857, this marble head was once part of an acrolith — a composite sculpture combining various materials, commonly used in Classical antiquity.

Viewed up close, the oxidized bronze eyelashes lend the eyes a haunting, almost mournful expression, as if streaks of mascara have traced silent tears down her cheeks. To borrow Shakespeare’s words from Venus and Adonis:

But hers, which through the crystal tears gave light,

Shone like the moon in water seen by night.

7. Piraeus Athena, fourth century BC

This bronze statue was uncovered in 1959 by workers who were drilling underground to install pipes in Piraeus, Greece. The sculpture, a depiction of the goddess Athena, is over-life-sized, standing at 2.35 meters (approximately 8 feet).

8. The Riace bronzes, 460–450 BC

Discovered in 1972 off the coast of Riace, southern Italy, these two remarkably well-preserved warriors are among the rarest surviving examples of ancient Greek bronze sculpture. In later periods, artworks like these were often melted down and lost to history.

The older warrior, missing one eye entirely, makes you realize just how much a fully preserved gaze would have transformed the impact of the entire sculpture.

In The Conduct of Life, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote:

An eye can threaten like a loaded and levelled gun, or can insult like hissing or kicking; or, in its altered mood, by beams of kindness, it can make the heart dance with joy.

A nice little exploration. Thank you.

Thought provoking! You made me look with new eyes - at eyes! Thank you!